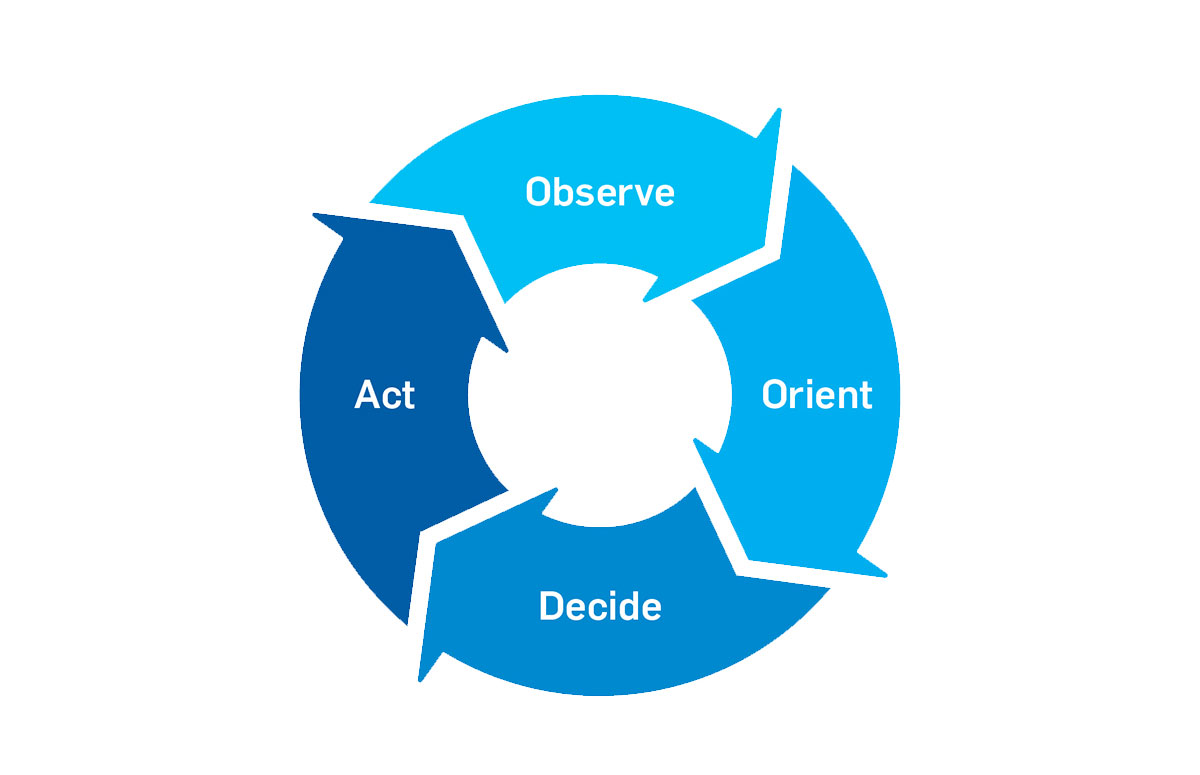

If you haven’t heard of the OODA loop you’re not alone. The OODA loop was developed by United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd in 1961 during a time when he authored the “Aerial Attack Study” often referred to as the “bible of air combat”. The acronym stands for Observe-Orient-Decide-Act and describes the pathway our brains use to deal with tactical decision making. The OODA Loop is a 4-step decision-making process where the person who makes it through all of the stages quickest, wins. He applied the concept to aerial combat operations to gain the upper hand on enemy pilots but the same theory can apply to the fire service.

Observe: The first step is to identify the threat and gain an overall understanding of the environment. In the fire service, this can be equated to a 3600 or scene size-up. The key point during the observation phase is recognizing that the situation is complex. Personnel must gather whatever information is available as quickly as possible in order to be prepared to make decisions based on it.

Orient: The orientation phase involves reflecting on what has been identified during observations and considering what should be done next. It requires situational awareness and understanding in order to make a good decision. Some decisions are instinctual therefore this step involves considering what and why decisions are made prior to choosing the best course of action. This is what we usually refer to as “deer in the headlights” when personnel are taking in the information in and trying to decide what the next move is.

Decide: The decision phase makes suggestions towards an action, taking into consideration all of the potential outcomes. For example, “If we break this window what will happen next” or “If we cut this part of the vehicle will it rollover?”. This is where personnel utilize their training and experience to recall decision made in the past that have worked. If they are unable to find similar experiences they will most likely choose whichever action they feel will work best, not always the most appropriate.

Act: The action phase pertains to carrying out the decision and related changes that need to be made in response to the decision. Personnel will utilize their ability to carry out tasks which they have learned in training or developed on the job.

It is rare to run a call where there aren’t outside stimuli that effect our concentration and ability to perform skills. One great example is the vehicle accident where multiple people are yelling for help, car horns are sounding, incoming apparatus are loudly announcing their arrival, etc. All of these things will interrupt our OODA loop and cause us to reset and reorient to the task we are performing. By utilizing this concept in training we can actually reduce the amount of time it take for our personnel to “reset” and continue on with their assigned task.

During any evolution take a moment to design “OODA loop pauses”. For example, as a student is getting ready to deploy a hose line, have another member run up screaming that their child is trapped on the 2nd floor even to the point of grabbing an air pack strap or coat collar (the better the acting, the better the outcome). The first time this happens, the firefighter deploying the hose line will likely freeze and not know what to do. You have just interrupted their OODA loop. At this point you can pause for a second to explain the way you want the student to behave and how they can overcome the distraction.

As you move on through different evolutions change up the way in which you interrupt the students, capitalizing on all the components of the OODA loop. After time you will notice that students react in the desired way and the task is carried out with little to no interruption. This can be extremely beneficial when dealing with complex or large incidents but is just as applicable to something like a medical call with one patient.

While not only reducing stress, it also allows for more solid foundations. This theory can be applied to fire, EMS, rescue, hazardous materials, even public relations training. The end result is that our personnel will be better prepared to respond to the ever-changing environments we face in a manner which we expect them too.

By: David Mellen

By: David Mellen

Mellen is a 20-year student of the fire service, and has been a Paramedic for 15 years. David currently serves as career Firefighter/Paramedic with the Edwardsville (KS) Fire Department in addition to serving as a volunteer Captain with the Reno Township (KS) Fire Department. He teaches as a lab instructor for the Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, KS and has sat on several review committees for fire service training publications. Mellen is a returning instructor at FDIC, Firehouse Expo, and several other state and local fire schools as well as the owner of Valor Fire Training.